Process stability stands as a cornerstone of chemical engineering education. It is not merely a theoretical concept found in textbooks; it is the critical difference between a smooth-running operation and a catastrophic failure in real-world industrial settings. For educators, the challenge lies in translating complex dynamic behaviors and control theories into tangible, understandable lessons that students can grasp and apply. When students understand stability, they learn how to predict system responses, maintain safety protocols, and optimize production efficiency. This guide explores effective strategies to impart this essential knowledge, ensuring the next generation of engineers is equipped to handle the volatile nature of chemical processes.

1. Grounding Theory in Real-World Disasters

One of the most powerful ways to teach the importance of process stability is to study what happens when it is lost. Case studies of historical industrial accidents, such as the Flixborough disaster or the Bhopal gas tragedy, serve as sobering reminders of the stakes involved. By analyzing the “why” and “how” behind these events, students can see the direct link between theoretical stability criteria—like the Routh-Hurwitz criterion or Bode plots—and actual safety.

Instructors should encourage students to deconstruct these events to identify the exact moment a process became unstable. Was it a runaway reaction? A failure in the cooling loop? A sensor malfunction? This forensic approach moves the conversation from abstract mathematics to critical thinking and risk assessment. It instills a safety-first mindset, emphasizing that process stability is not just about keeping a graph flat; it’s about protecting lives and infrastructure.

2. Leveraging Simulation Software for Dynamic Learning

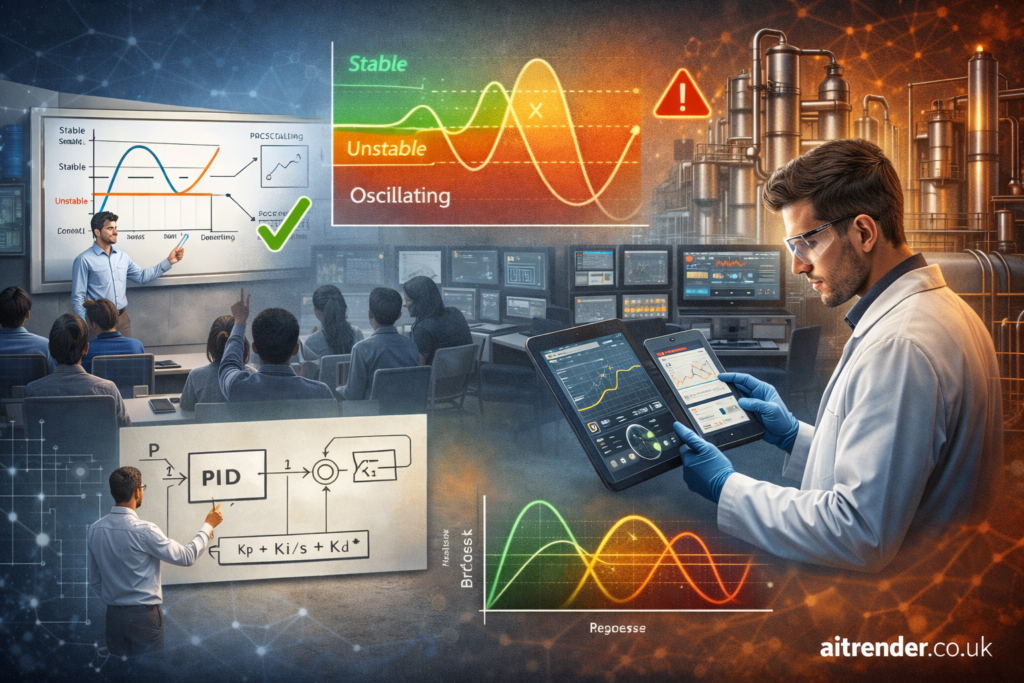

Static diagrams on a whiteboard can only convey so much about dynamic systems. Simulation software allows students to visualize how variables interact in real-time. Tools like MATLAB/Simulink or ASPEN Plus enable students to model reactors, distillation columns, and heat exchangers, and then introduce disturbances to see how the system reacts.

An effective exercise involves asking students to tune a PID controller within a simulation to stabilize a fluctuating system. They can experiment with gain, integral, and derivative settings to witness how aggressive tuning might lead to oscillations or how sluggish tuning results in poor disturbance rejection. This hands-on experimentation builds intuition. Students learn that stability often requires a trade-off between speed of response and robustness, a concept that is difficult to grasp through equations alone.

3. Emphasizing the Role of Chemical Additives in Stability

Often, stability is taught strictly as a mechanical or control systems issue, ignoring the chemical realities inside the vessel. However, chemical interactions, such as foaming, can severely disrupt process control sensors and hydraulic balance. This is where the practical application of chemical aids comes into play.

For instance, in fermentation processes or wastewater treatment, uncontrolled foam can cause level sensors to give false readings, leading to system in process stability. Educators can introduce the role of defoamer manufacturers who create specialized chemical agents to mitigate these physical disturbances. By discussing how additives like antifoams, stabilizers, or corrosion inhibitors work, students gain a holistic view of process stability. It teaches them that sometimes the solution to an in stability problem is not a better control algorithm, but a chemical intervention to alter the physical properties of the fluid.

4. Integrating Laboratory Experiments with Feedback Loops

Nothing reinforces a concept like physical observation. Simple laboratory setups, such as a tank level control experiment or a temperature control loop in a stirred tank heater, provide immediate visual feedback. When students physically turn a valve or adjust a heater power setting and watch the temperature gauge overshoot and oscillate, the concept of “in stability” becomes tangible.

To maximize the impact of these labs, instructors should introduce intentional faults. Block a sensor, introduce a sudden load change, or simulate a valve sticking. Watching the system drift away from the setpoint forces students to diagnose the in stability in real-time. This mirrors the troubleshooting they will face in their careers. It also highlights the importance of sensor placement and the physical limitations of actuators, bridging the gap between idealized textbook models and the messy reality of physical hardware.

5. Focusing on Nonlinear Dynamics and Multiple Steady States

Introductory courses often focus on linear systems because they are easier to solve mathematically. However, most real chemical processes are inherently nonlinear. Exothermic reactors, for example, can exhibit multiple steady states—some stable, some unstable. Teaching students to identify these regimes is crucial.

Using graphical methods like van Heerden diagrams helps students visualize heat generation versus heat removal. They can see how a reactor might operate safely at a low temperature, but a small disturbance could push it past a “point of no return” into a high-temperature, runaway state. Discussing bifurcation theory in this context helps advanced students understand how changing a single parameter, like cooling water flow rate, can fundamentally change the stability landscape of the entire process. This prepares them for complex industrial environments where linear approximations often fail.

6. Project-Based Learning: Designing for Stability

Finally, the synthesis of all these concepts should occur in a capstone design project. Instead of just designing a plant for steady-state operation at optimal conditions, challenge students to perform a operability and hazard analysis. Ask them to prove that their design can recover from specific disturbances, such as a power failure or a feed composition change.

In these projects, students must select appropriate control strategies and safety interlocks. They might discover that their highly efficient reactor design is practically uncontrollable because it operates too close to an unstable region. This realization—that an efficient design is useless if it cannot be kept stable—is perhaps the most valuable lesson of all. It forces them to prioritize robustness and controllability alongside yield and profit, molding them into responsible, practical engineers.

Conclusion

Teaching process stability requires a multifaceted approach that blends rigorous theory with practical application. By examining historical failures, utilizing advanced simulation tools, acknowledging the role of chemical additives, and engaging in hands-on experimentation, educators can demystify complex dynamic behaviors These strategies ensure that students graduate not just with the ability to solve differential equations, but with the deep, intuitive understanding necessary to design and operate safe, stable, and efficient chemical processes.